After a wound (from injury, surgery or burns), your body goes through a healing journey. Most wounds heal well, and form healthy scars, but sometimes extra tissue, tightness, or raised texture can develop. Understanding how wound heal and scars form (and what can go wrong) helps you work with your body to improve comfort and function. It is also important to bear in mind that even the most optimal and well healed scar will only have around 80% functional quality in comparison to healthy tissues,

WOUND HEALING & SCAR FORMATION STAGES

1. Haemostasis

(Stopping the Bleeding)

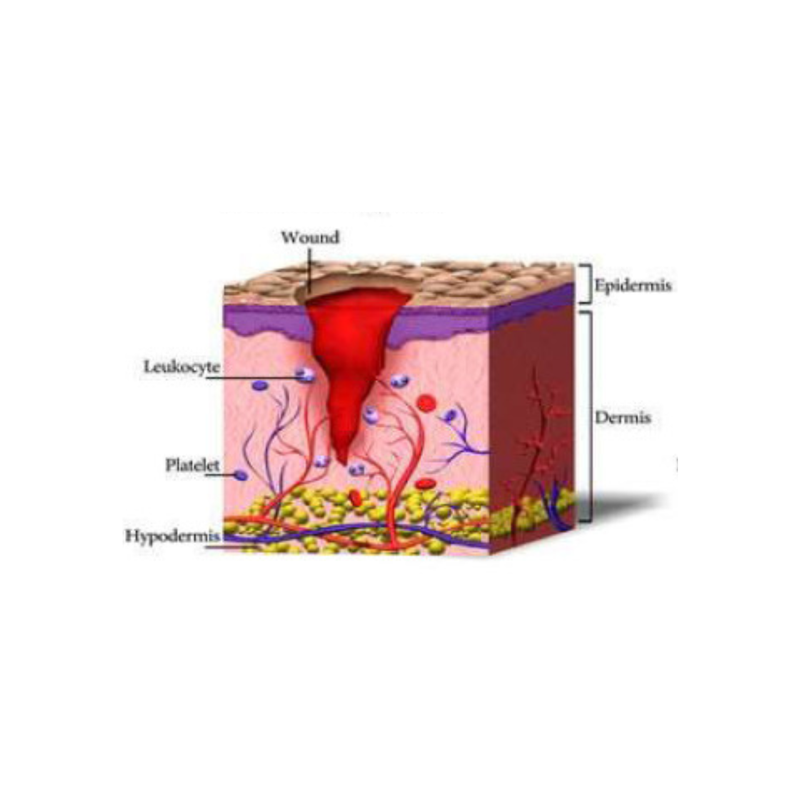

Right after the injury, your body works to stop the bleeding. Blood vessels constrict, platelets form a clot, and a temporary “plug” (fibrin clot) forms. This protects the wound and begins the healing process.

This stage typically starts within minutes and lasts up to 24hours.

2. Inflammation

(Cleaning Up & Protection)

Soon after, immune cells (like white blood cells) enter the wound to clean out bacteria, dead cells, and debris. You might see swelling, warmth, redness — this is your body working to protect you.

This stage starts usually day 1 to 3 and can last up to 1 week.

3. Proliferation

(Building New Tissue)

In this phase, new blood vessels form, skin cells and connective tissue (fibroblasts) make new collagen, and the wound starts to fill in. The skin edges begin to cover the wound (epithelialisation). This is when scars begin forming more visibly.

This stage starts around day 4 and will last up to 21 days gradually progressing to the next, maturation stage of scar formation.

4. Remodelling

(Strengthening & Softening)

Over weeks and months (sometimes up to a year or more), the new tissue becomes more mature. Collagen gets reorganized, excess tissue may reduce, and the scar gradually becomes softer, flatter and less red or pink.

This stage starts around day 21 and can lasts for months or even years.

WHAT AFFECTS SCAR FORMATION?

-

Size and depth of the wound – Deeper or larger wounds are more likely to leave visible scars.

-

Location on the body – Areas with more movement or tension (like joints) may scar more noticeably.

-

Wound care – Proper cleaning, protection, and following care instructions can support better healing and reduce scarring.

-

Infection or delayed healing – These can interrupt normal healing and increase the risk of scarring.

-

Skin type and tone – Some skin types are more prone to raised or pigmented scars (e.g. keloids or hypertrophic scars).

-

Age – Younger skin tends to heal faster but may scar more easily, while older skin may heal more slowly.

-

Genetics – Family history can play a role in how your skin heals and forms scars.

-

Overall health – Conditions like diabetes or poor nutrition can affect wound healing and scar formation.

-

Repeated trauma – Rubbing, stretching, or bumping the wound during healing can worsen scarring.

PATHOLOGICAL SCARS

When healing goes off the track

Most wounds heal naturally, leaving a flat, pale scar that fades over time. However, some scars become thicker, raised, or continue to grow — these are called pathological scars. They happen when the body’s healing process works too hard, making too much of the tissue (mainly collagen) that repairs the skin.

There are two main kinds of pathological scars: hypertrophic scars and keloid scars.

Hypertrophic scars are raised, red, and sometimes itchy scars that stay within the area of the original wound. They often appear after burns, surgery, or deep cuts.

Why They Happen:

When the skin heals, it produces collagen to close and strengthen the wound. In hypertrophic scars, the body makes too much collagen, which causes the scar to thicken.

Can They Be Prevented?

Good wound care can help. Keeping the area clean, avoiding tension or pulling on the wound, and using silicone gel or silicone sheets can reduce the risk. Some people may also benefit from pressure dressings after surgery.

Treatment Options:

These scars often get better with time. If not, treatments such as silicone therapy, steroid injections, laser therapy, or microneedling can help make the scar flatter, softer, and less noticeable. Gentle scar massage following the Restore scar therapy techniques can also improve the symptoms.

Keloid scars are thicker and grow beyond the edges of the original wound. They can be shiny, firm, and darker than the surrounding skin. Some may cause itching, pain, or sensitivity.

Why They Happen:

In keloids, the healing response doesn’t “switch off,” and the body keeps making collagen even after the wound has closed. They are more common in darker skin tones and often appear on the chest, shoulders, upper back, and earlobes.

Can They Be Prevented?

If you’ve had keloids before, try to avoid unnecessary skin injury — such as piercings or tattoos — especially on areas prone to keloids. After surgery or injury, your doctor may recommend silicone therapy or pressure dressings early on.

Treatment Options:

Keloids are stubborn but can be managed. Options include steroid injections, laser treatment, cryotherapy (freezing), pressure therapy, or surgical removal combined with other treatments to reduce recurrence.

OTHER TYPES OF SCARS & SCAR RELATED PROBLEMS

Not all troublesome scars are “pathological.” Some scars heal in the usual way but can still cause problems later on. These scars may affect how your skin feels, moves, or looks — sometimes long after the wound has closed.

It’s important to remember that the visible part of a scar is only the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface, scar tissue can extend through the deeper layers of skin, fascia (the body’s connective tissue), muscles, and tendons. When these layers become tight or stuck together, it can affect movement, posture, and even how nearby joints or muscles work.

In some cases, deeper scars — especially after abdominal or pelvic surgery — can influence the digestive or reproductive systems by creating tension or pulling in the connective tissue that links everything together. Scars can even cause pain or restriction away from the scar itself, as the body compensates for lost flexibility in one area.

Understanding these effects helps explain why gentle scar massage, movement therapy, and early care can make such a difference in recovery — not just for how a scar looks, but for how your whole body feels and functions.

ATHROPHIC SCARS

What They Are:

Atrophic scars are sunken or pitted scars where the skin heals with less tissue than before. Common examples include acne scars or scars left after chickenpox.

Why They Happen:

The skin doesn’t make enough collagen during healing, leaving a small dip or hollow.

Can They Be Prevented?

Good wound care, avoiding picking or squeezing spots, and treating acne early can reduce the risk.

Treatment Options:

Atrophic scars can be improved with microneedling, laser therapy, chemical peels, or dermal fillers that raise the skin’s surface.

TIGHT OR SHORTENED "ROPEY" SCARS

What They Are:

Some scars become tight or thick, creating a cord-like or banded feeling under the skin. This can limit movement, especially near joints.

Why They Happen:

When healing tissue contracts, it can pull the surrounding skin and deeper tissues, reducing flexibility.

Prevention & Treatment:

Keeping new scars moisturized and gently massaging them can help. If tightness develops, scar massage, stretching, silicone therapy, or manual therapy from a trained therapist can restore movement. In some cases, surgery or laser release may be needed.

CORDING (SCAR BANDS)

What It Is:

Cording feels like a thin, tight string under the skin — often seen after surgery, especially breast or underarm surgery.

Why It Happens:

Scar tissue forms along lymph or connective tissue lines, restricting movement and causing discomfort.

Treatment Options:

Physiotherapy, gentle stretching, and manual therapy are often very effective. Most cords soften and resolve over time with guided care.

ADHESIONS

What They Are:

Adhesions occur when scar tissue sticks to deeper layers — muscles, tendons, or organs — instead of gliding freely. This can cause pulling, pain, or restricted movement.

Why They Happen:

Adhesions form when the healing process joins tissues that should remain separate, often after surgery or burns.

Treatment Options:

Manual scar therapy, soft tissue release, or movement-based rehabilitation can improve mobility. Severe adhesions may need surgical correction.

IN SUMMARY

Even a small or “normal” scar can affect your comfort and movement if it becomes tight or stuck. Early attention, regular care, and guided therapy can help you recover not just the appearance of the skin, but the way your whole body feels and moves.